Videos For Final Fantasy Game Design

After switching over to the Famicom, there was a time when I wasn't happy with anything I was creating. I thought of retiring from the game industry and I created Final Fantasy as my final project. That's why the title includes the word 'final' but for me, the title 'Final Fantasy' reflects my emotional state at the time and the feeling that time had stopped. They say that technologically, it's good to keep going, and each time, we give it our all and expend our skills and energy until we can go no further; this is what I consider to be the 'final fantasy'.

Hironobu Sakaguchi[1]

Final Fantasy is a video game franchise developed and published by Square Enix. It is a Japanese role-playing game series with varying gameplay, settings and stories between each installment, retaining plot and gameplay elements throughout, focusing on fantasy and science fantasy settings. Though the core series is a role-playing game franchise, it has branched into other genres, such as MMORPGs, tactical role-playing games, action role-playing games, and fighting games. The series has been distributed on many platforms, beginning with the Nintendo Entertainment System, and including consoles, computers, mobile operating systems and game streaming services. The series has also branched into other forms of media, particularly films, novels, and manga.

The majority of the games are stand-alone stories with unique characters, scenarios and settings, though several spin-offs and sequels to main series games continue stories within the same worlds. The series is defined by its recurring gameplay mechanics, themes and features. Commonly recurring features include: the series' "mascot" creature, chocobos, that are often used as steeds; a character named Cid who is usually associated with engineering; moogles, cute, flying creatures that often aid the player by facilitating some manner of in-game mechanics; the mythology-based summoned creatures that can be called forth to aid players in battle and are also commonly fought as bosses; the job system, whereby playable characters are defined by their unique job classes; and the active time battle system, an evolution of the classic turn-based system common in early JRPGs, where a unit's speed determines how many actions they can take.

The series' plots tend to focus on a group of characters from various backgrounds who team up to save their world while dealing with their own struggles and fighting against a central antagonist whose goal is usually world destruction. Names, designs and spells are often based on real-world mythologies, religions and cultures.

The series is Square Enix's flagship franchise and their best selling video game series with 130 million units sold[2](as well as revenue earned through mobile releases and MMO subscriptions), and has made an impact in popular culture, particularly for popularizing the console RPG genre outside of Japan. Its critically acclaimed orchestral musical scores, memorable and likable characters, realistic and detailed graphics and innovative mechanics have made the franchise notable in the industry.

Contents

- 1 Gameplay

- 1.1 Battle

- 1.2 Growth

- 1.3 Equipment

- 1.4 Field

- 1.5 MMOs

- 1.6 Spin-offs

- 2 Synopsis

- 2.1 Settings

- 2.2 Plots

- 2.3 Themes

- 3 Development

- 3.1 Background

- 3.2 Design

- 3.3 Music

- 3.4 Technology

- 4 Reception

- 4.1 Critical reception

- 4.2 Accolades

- 4.3 Commercial performance

- 4.4 Pop culture and legacy

- 5 Notes

- 6 References

- 7 External links

Gameplay [ ]

The Final Fantasy series usually puts the player in control of multiple characters in a party, though there are exceptions. The player will build the party's strength by gradually acquiring new abilities and equipment to handle more powerful opponents. In many games this task extends beyond the main story with challenging superbosses and bonus dungeons serving as optional tests of skill. As a Japanese role-playing game, many installments—particularly the earlier installments in the main series, or the throwback spin-offs returning to old formulas—involve frequent use of menus to select items, skills and upgrades.

Battle [ ]

Basic battle in Final Fantasy VI.

Battle systems have varied with the majority being menu-based with variants on turn-based combat, though others use action-based combat systems. Earlier installments have instanced battles based on random encounters while roaming the world map, while some later games (beginning with Final Fantasy XII in the single-player main series games) have free-roaming enemies that are engaged without transition. Battle commands typically feature a basic physical attack with the equipped weapon(s), a magic skillset (with magic spellsets featuring a tiers naming system), other special command abilities (such as Steal or Throw, or a skillset such as summoning monsters), and a set of items, though the player may also try to flee from many normal encounters. The characters normally have an HP and MP stat (though some games ignore MP), where HP determines the damage characters can take before they are KO'd while MP determines how many spells or other abilities a character can use. Most games also feature elements and status effects, nuances which can affect the course of a battle, with enemies and allies using them to attack and exploit each other's weaknesses and/or to defend themselves, as well as to prepare for an upcoming encounter.

The best known and widely used battle system is the Active Time Battle pseudo-turn-based system introduced in Final Fantasy IV where characters can perform an action when their ATB gauge is full. The fill rate is affected by stats, status effects, abilities used and other factors requiring the player to be economical with time. Many games feature a variant of this system. As an early example, Final Fantasy XII uses the Active Dimension Battle system to determine the rate at which characters will perform actions input through menus or the gambit system; there are no random encounters, and the player can move the character around the field and must be within the range of the enemy they are using their skill on.

Basic battle in Final Fantasy XII.

The Final Fantasy series has also featured a more basic, traditional turn-based system, such as the original Final Fantasy through to Final Fantasy III that do not rely on time, but the player and the enemy party take turns executing commands. Final Fantasy X features a Conditional Turn-Based Battle system where turns are taken based on an Act List, the turn order depending on the units' stats and statuses, and commands being ranked usually with stronger commands having longer "recovery time" until the unit can act again.

Outside of turn-based systems, the series has occasionally featured purely action-based combat systems, in which the skills the characters use are still similar to traditional skillsets of attacks, magic spells, special abilities and items, but the rate the characters use these abilities depends on player skill with less reliance on menus. The first in the main series with an action role-playing game focus is Final Fantasy XV, though many spin-offs, such as Crisis Core -Final Fantasy VII- and Final Fantasy Type-0, have used these systems before.

Growth [ ]

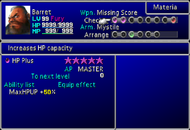

Materia menu in Final Fantasy VII.

Character growth determines how player characters learn new abilities and boost their stats. Unlike battle systems, character growth systems are less consistent throughout the series, and players must internalize the systems to make the correct decisions. The only consistent character growth mechanic used in the series has been the level based system where characters raise their level through experience points earned in battle to improve stats and sometimes learn new abilities. Even this system has been excluded from some games, such as in Final Fantasy X and Final Fantasy XIII, where only ability points are accumulated from battles that can be expended for both better stats and new skills.

One of the most common and familiar systems that determines character growth is the job system, a class-based system where players assign characters a job, choosing from series staples such as Black Mage, White Mage, Monk, Thief and Warrior, among many. The character's job determines their base abilities and the stats gained. Throughout earlier games, this was often through experience, though Final Fantasy V introduced ability points as a separate system where the experience would increase a level independent of the job, and the ability points likewise accumulated from battles are used to grow the job's abilities. Many games featuring the job system allow the player to switch the jobs around to learn new abilities or face new enemies, though some, such as the original Final Fantasy, stick the job as fundamental to the character. Similarly, games such as Final Fantasy IX, do not have named job systems, but the characters have defined roles similar to the job system with pre-determined abilities they can learn.

Job select screen in Final Fantasy V.

Many games offer different systems to allow more freedom when growing characters' abilities and stats beginning as early as Final Fantasy II. Often this features a mix of the ability points system, in which points are used to grow abilities without being determined by a job. One of the popular systems is the Materia system featured in Final Fantasy VII and other games in its sub-series, where the player equips characters with Materia that contain various command or support abilities, and accumulating ability points allows the Materia to grow and gain stat boosts and new abilities. Similarly, the magicite featured in Final Fantasy VI allows the player to equip magicite remains of espers with the accumulated ability points allowing the characters to learn the magic spells they contain, and once reaching a certain threshold the character learns the ability permanently to use it even without the equipped magicite. This way the player can directly control which party members use which skills and customize their party to their preferred play style.

Other games in the series deviate further from the typical formula. Final Fantasy XII has player characters learn License Points (a variation of the ability points system) to spend on a License Board to purchase "licenses" to wield different equipment, use different spells and boost stats, with total freedom. In the International Zodiac Job System re-release the License Boards are based on jobs. In Final Fantasy X characters learn abilities based on a Sphere Grid that begins linearly but the player can eventually branch the grid out further, and potentially max all stats with various items usable to alter and improve Sphere Grid growth. Another example featuring items for growing skills is Final Fantasy VIII where magic spells are collected into an inventory similar to items, and acquired through refine or draw abilities, with other abilities learned via ability points from the character's equipped Guardian Forces.

Equipment [ ]

Equipment menu in Final Fantasy IV.

Typically, characters can equip armor, weapons and accessories, where armor provides defensive boosts, weapons determine the strength and type of the attacks used, and accessories provide various supporting abilities or bonuses. There are rarely optimal sets of armor or accessories, though many games feature ultimate weapons for each character, often involving sidequests to obtain them.

Games can deviate from the standard format. Final Fantasy VI features relics as accessories, while Final Fantasy VIII has neither accessories nor armor, all effects typically associated with gear being abilities instead. Many games feature specific types of armor, such as head armor, body armor, arm armor or leg armor, while other games only have a single set of armor based on the character, such as Final Fantasy VII or Final Fantasy X. Armor can provide bonus abilities, such as resistances to status effects or elements, and in some games, such as Final Fantasy IX, are integral to the character growth system where characters learn new skills by equipping gear.

Field [ ]

World map exploration in Final Fantasy IX.

Outside of battles the player can explore the field for items, dialog with non-player characters, and for trading in gil for items and gear. In games featuring instanced random encounters, the party will encounter an enemy randomly while exploring dangerous areas (though abilities to reduce the encounter rate can be learned), while games with free-roaming enemies have enemies appear in the dangerous areas for the player to engage or avoid.

The player can explore dungeons where enemies are fought and treasures and items can be found. Enemies tend to be more numerous in dungeons, and there is often a boss at the end. Other areas are safe havens, notably towns, which contain shops for the party to buy new items and equipment, and often an inn to rest at and fully restore HP and MP. Many games feature a world map used to traverse on foot or via airships, chocobos or other vehicles. World maps have random encounters and are crossed to reach other points of interest in the world, often with mountains and oceans and other impassable objects placed to ward off areas the player is not meant to visit yet; by end game players usually acquire a vehicle that allows exploration of every nook of the world.

Dialog with NPCs in Final Fantasy XII.

The field areas often feature non-player characters and events that allow the player to play minigames, for mandatory or non-mandatory rewards. The first major minigames were introduced in the Gold Saucer in Final Fantasy VII where the player can play various games including chocobo racing and battle arena. Another notable minigame was the Dragon's Neck Colosseum in Final Fantasy VI where the player can bet items for rewards and fight various enemies. Card minigames are also popular, particularly Triple Triad introduced in Final Fantasy VIII, which has seen many iterations in following releases.

MMOs [ ]

Menus in Final Fantasy XIV.

Though the MMO releases, Final Fantasy XI and Final Fantasy XIV, are members of the main series, with the exception of some abilities, some equipment, and the job system, they deviate from the traditional gameplay format due to their nature as games of a different genre. The MMOs are free-roaming with enemies appearing on the field, rarely use traditional menu systems (instead abilities are selected from a player-customized list) and use various features typical of MMO games. Being multiplayer games they include player interaction as well as trading between players. The player does not control a party, but multiple players can form one to fight in dungeons and against bosses.

Spin-offs [ ]

Battle in Dissidia Final Fantasy.

The spin-offs' gameplay can deviate a lot from the main series. While spin-offs tend to include gameplay fundamentals, if only in abilities and ability names, many stick to role-playing game elements. As an example, although Dissidia Final Fantasy and games following its format are fighting games, they still feature character growth, characters using their specific abilities, and similar equipment systems. Another notable spin-off, Final Fantasy Tactics, is a tactical role-playing game with a job system that uses tactical unit command as opposed to one of the battle systems featured throughout the main series. Many games also feature action elements, such as Final Fantasy Type-0, while others include shooting elements, such as Dirge of Cerberus -Final Fantasy VII-, but still keep the series fundamentals.

Many spin-offs have been released on mobile platforms that use simplified forms of typical battle systems, such as Final Fantasy Record Keeper. Other games use collectible card gameplay, barely reminiscent of the main series.

Synopsis [ ]

Settings [ ]

Alexandria, a city in Final Fantasy IX.

The Final Fantasy series' settings range from traditional fantasy to science fantasy. Each game focuses on one world that vary dramatically in backstory, technological advancement, and culture. Humans are the dominant sapient species, with chocobos, moogles, and several enemy species being the most commonly recurring non-humans. The worlds often feature Crystals that throughout early settings were magical phenomena fundamental to the elements of the worlds, but in others have different roles.

Settings often contain elements based on real-world mythology, and the series features many allusions to religion. A notable example are ancient mythological creatures that function as summons, and have various different roles within the game lores. Espers from Final Fantasy VI are a magical race that once lived alongside humans until a war wiped most of them out. Aeons in Final Fantasy X are the physical realizations of the dreams of the fayth, and summoners use them to battle Sin. Many games featuring summoned monsters do not have them as a named race, or give them a key role within the lore, the summons being merely abilities to be used in battle.

Midgar, a city in Final Fantasy VII.

The series often features other mythological references, such as Kefka Palazzo and Sephiroth's godforms based on divinity as their final encounters in Final Fantasy VI and Final Fantasy VII. The game worlds themselves are commonly based on real-world mythology, such as Final Fantasy X and its Shinto and Buddhism influences, and the influence of Jewish mysticism in Final Fantasy VII.

Each setting often features some form of magic (sometimes spelled magick), though it often differs between the different lores. In many settings, magic is the power of the world's Crystals. In Final Fantasy VI magic has become a rarity, with many resorting to magitek (magic technology). In Final Fantasy VII, magic is a product of the Lifestream and can be used via Materia, though scientists have stated that "magic" is an unfitting term for a force of nature. In Final Fantasy XII, magick is provided by the mysterious substance known as Mist that seeps from the inside of the planet.

Plots [ ]

The characters resting in Final Fantasy X.

The series' most basic plots revolve around the cast fighting an antagonist who aims to destroy or conquer the world while coping with their own struggles. The characters are often part of a small resistance against one or more larger powers, and each tend to have different motivations within their own groups. There is a sense of desperation, as the characters fight for everything they hold dear. The plots vary from being overall light-hearted, such as Final Fantasy III or Final Fantasy V, to being more grim and realistic, such as Final Fantasy II or Final Fantasy VII, though many, such as Final Fantasy IX and Final Fantasy XIV, are a mix.

For the first few installments a key plot point was the Crystals. Each world would feature four, each representing the four elements, and without them the world would deteriorate. The antagonists often begin by destroying or stealing these Crystals for power, and the party would fail to prevent them and be forced to foil their grander scheme later. This plot was abandoned in Final Fantasy VI, and while the games would still feature Crystals, they often did not have the same importance.

The Crystal-theme can be said to be the overarching theme of the series, as a traditional Final Fantasy plot involves an antagonistic force trying to make use of the Crystals' power with the player power in opposition, sometimes chosen to wield the Crystal's power to enact their will as the Warriors of Light. Some games subvert this theme, such as Final Fantasy XII—where the Crystals are called nethicite—and the Fabula Nova Crystallis: Final Fantasy series with its various types of Crystal, showing that the power of the Crystals is not necessarily something that mankind should pursue despite its might.

Themes [ ]

Protagonist Cloud Strife fights antagonist Sephiroth in Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children, an example of dualism and contrast.

One key theme in the series is dualism, presented in many ways, such as through a contrast between two worlds, between two heroes/heroines, and between a protagonist and an antagonist. Most often this dualism represents a balance that is disturbed by outside forces, forcing the protagonists to restore it. Other times, the "balance" set is deemed unjust by the protagonists and they must instead end the cycle to free the world.

Another common theme is rebellion. The protagonists are often forced to fight a higher power either on a quest for revenge, for freedom or another motivation. The higher power can range from an empire, such as the Gestahlian Empire from Final Fantasy VI, a religion, such as Yevon from Final Fantasy X, or a deity, such as the fal'Cie from Final Fantasy XIII. During the journey to vanquish these powers their threat escalates, until the protagonists free the world of the oppressor(s).

Development [ ]

Background [ ]

During the mid 1980s, Square Co., Ltd. entered the video game industry by developing games for the Nintendo Famicom. In 1986, Enix released its first Dragon Quest game and popularized the RPG genre in Japan (after western games, such as the Wizardry series, introduced them to Japanese audiences). Coupled with Nintendo's Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda, Dragon Quest was one of the defining games of the Famicom system.

Square had been developing simple RPGs, pseudo-3D games and racing games, although they failed to compete with the market, and did not perform well commercially. Series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi and his team grew pessimistic at the failures as the company faced bankruptcy, so he began to develop the RPG Final Fantasy as a personal final project to leave a legacy; if the game had sold poorly, he would have quit the industry to return to university.[3]

Sakaguchi wanted the game to have a simple abbreviation in the Roman alphabet (FF) and a four-syllable abbreviated Japanese pronunciation (efu-efu). "Fantasy" was chosen due to the setting, though "Final" was originally intended to be "Fighting", and was changed to avoid conflict with the tabletop game Fighting Fantasy.[4] Though Final Fantasy was released at a time when competing games, such as Sega's Phantasy Star and Dragon Quest III, were released, it pulled Square out of its financial crisis, and when released three years later in North America, outsold several of its peers.

As Final Fantasy had not been planned with a sequel in mind, Final Fantasy II was developed in a new world separate to the first with new characters designed by Yoshitaka Amano, and given a deeper story to match competitors such as Phantasy Star II.[3]

Although not the first game to be released outside of Japan, Final Fantasy VII was the first overseas to popularize the series, and the JRPG genre.[5] [6] Although the game is still the best-selling game in the series, with over 11 million units sold between its original release and subsequent re-releases,[7] the series has continued to find financial success since and has become the company's best-selling franchise worldwide.[2]

From the very beginning Final Fantasy was the fruit of a team effort. To compete with games like Dragon Quest or Mario Bros., both of which showed the presence of highly talented individuals, Sakaguchi realized Square would need to aggregate the energies of multiple people, growing into a tradition of sorts. Working as a team enabled the incorporation of CG into the games. Sakaguchi has lamented that if Final Fantasy had been more of a solo effort, the series might have looked quite different.[8]

Design [ ]

Artwork of Terra Branford by Yoshitaka Amano.

Character concept artwork was handled by Yoshitaka Amano from Final Fantasy to Final Fantasy VI who also handled logo and promotional image designs for games to follow. He was replaced by Tetsuya Nomura from Final Fantasy VII onwards (with the exception of Final Fantasy IX—where it was handled by Shukō Murase, Toshiyuki Itahana and Shin Nagasawa—and Final Fantasy XII—where it was handled by Akihiko Yoshida).

Gameplay systems were originally based on those seen in RPGs released at the time the series was developed, though many systems which would become series staples were designed by Hiroyuki Ito. Ito developed systems, such as the Active Time Battle system inspired by Formula One racing (the concept of different character types being able to "overtake" each other). Ito refined the job system in Final Fantasy V to become the system used frequently throughout the series, and designed the Gambits system for Final Fantasy XII.[9] Other systems, such as the Materia system in Final Fantasy VII, were designed as a group effort, and was designed so the combat changed depending on how the Materia was used, as opposed to characters having innate skills.[10] Toshiro Tsuchida would design systems for other games, such as the removal of Active Time Battle in Final Fantasy X to replace with conditional turn-based battle, and later designed the Command Synergy Battle system for Final Fantasy XIII to make battles appear as visually impressive as in the movie Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children.[11] The MMO gameplay systems have been drastically different, but mostly drawn inspiration from a mix of the Final Fantasy games and from other games in the genre.

Stories have been worked on as a collaborative effort from multiple developers with concepts having drawn inspiration from multiple sources. In the early games, Sakaguchi drew inspiration from anime film maker Hayao Miyazaki, and staples such as chocobos and airships originally derived from them.[12] Furthermore, many have noted similarities between the series and Star Wars, present in references such as Biggs and Wedge and in recurring plot points such as an "Empire".[13] The series contains many darker themes of tragedy and loss, many inspired by the developers' own experiences. While developing Final Fantasy VII, the series creator Sakaguchi's mother died, which caused him to drastically reform the game's story to be about coping with loss.[14]

The series has had multiple directors: Sakaguchi directed the first five installments, Yoshinori Kitase and Ito collaboratively directed Final Fantasy VI, and the two went on to direct many later installments on their own. Ito directed Final Fantasy IX and Final Fantasy XII, while Kitase developed Final Fantasy VII, Final Fantasy VIII and Final Fantasy X. After Final Fantasy X Kitase decided to stop directing but remained involved as a producer instead, choosing Motomu Toriyama as the director for Final Fantasy XIII and its sequels. The MMO releases have had multiple directors, though most recently, Naoki Yoshida has directed Final Fantasy XIV. Hajime Tabata started with directing spin-off games for portable gaming systems with Before Crisis -Final Fantasy VII- and Crisis Core -Final Fantasy VII-, but when Final Fantasy Versus XIII became Final Fantasy XV Tabata took over the role of director.

Music [ ]

Nobuo Uematsu (middle) and The Black Mages, a hard rock band that has released three albums of arranged Final Fantasy music.

The majority of the music in the series—including the main recurring themes, and the full official soundtracks for the first ten games in the main series—was composed by Nobuo Uematsu, and has been praised as one of the greatest aspects of the series.[15] [16] [17] The music has had a broad musical palette, taking influences from classical symphonic music, heavy metal and techno-electronica.

Each game typically features themes for different locations (or types of locations), story events, characters and battle themes (typically a basic battle theme, boss battle theme, and a final boss theme, as a minimum, with some special bosses having their own battle themes). There are many recurring themes, such as the "Chocobo Theme" associated with the series "mascot" creature, main series theme that has often played in the intro or in the ending credits, the "Victory Fanfare" that concludes won battles, "Prelude", also known as the "Crystal Theme" that has become one of the series' most recognizable themes, and "Battle at the Big Bridge", the boss battle theme of the recurring character Gilgamesh. Themes have often been rearranged for their appearances within different games to suit the various settings.

From the beginning Uematsu was given creative freedom, though the series' creator Hironobu Sakaguchi would request specific set-pieces to fit themes, and early on there were specific notes Uematsu was unable to use due to hardware limitations.[18] From Final Fantasy IV onwards, he had more freedom of instrumentation. For "One-Winged Angel", the Final Fantasy VII final boss theme and the series' first vocalized theme, Uematsu combined both rock and orchestral influences having had no prior training in orchestra conduction.[18]

The developers had originally planned to use a famous vocalist in the ending of Final Fantasy VII, but the plan didn't go through due to being too abrupt, and there was no suitable theme in the story for a vocal song to suddenly come up in the ending. This idea was realized in Final Fantasy VIII whose "Eyes On Me" has a meaning in the plot and it relates to the game's main characters.[19] Uematsu went on to compose vocal theme songs for the main series games Final Fantasy IX, Final Fantasy X, Final Fantasy XII and Final Fantasy XIV, even though he didn't otherwise participate with Final Fantasy XII, its soundtrack being composed by Hitoshi Sakimoto.

From Final Fantasy X onward the series has had other composers as Uematsu eventually left Square to go freelance, though he has continued to compose music for the series for as recent as the original Final Fantasy XIV. The soundtrack for Final Fantasy X was a joint effort between Uematsu, Masashi Hamauzu, and Junya Nakano, the music for Final Fantasy XII was mainly composed by Hitoshi Sakimoto, Masashi Hamauzu did the soundtrack for Final Fantasy XIII, and Yoko Shimomura—who had previously composed the music for Square Enix's Kingdom Hearts series—composed the music for Final Fantasy XV.

The compositions' success has resulted in many side projects by Uematsu based on the music from the series. The Black Mages was a hard rock band that arranged and remixed music from the series. Other notable projects have included live orchestral tours Music from Final Fantasy, Final Symphony tours and the Dear Friends -Music from Final Fantasy- tour. Many rearrangement compilations have been released on the series' music, the Piano Collections being among the best known, with many games also having special orchestrated albums whose compositions have been performed in the live orchestral tours. Official sheet music books have been released in Japan, usually for piano arrangements of the in-game soundtracks.

Technology [ ]

Battle in Final Fantasy.

The first three titles where developed on the 8bit Nintendo Entertainment System while the next three were developed on the 16bit Super Nintendo Entertainment System. These games were two-dimensional and used sprites to depict characters and enemies on screen. The enemies in battle would have more detailed sprites that more closely resembled their artwork, but far fewer animations. The character sprites had several frames of animations, as well as different sprites based on their various statuses or weapons equipped, but were less detailed. Field sprites were less detailed than battle sprites. Though the SNES allowed games to have greater graphics and use higher-quality music with more instrumentation, the games were mostly the same format and similarly basic.

When transitioning to the 32bit era, Square began to develop games in 3D. A tech demo in 1995 using Final Fantasy VI characters, Final Fantasy VI: The Interactive CG Game, showed the kind of technology they were using. Square opted to develop on the PlayStation, as opposed to the Nintendo 64 as originally intended, due to its use of disc storage instead of the more limited cartridges,[20] and the game still required three discs of storage. Final Fantasy VII was the most expensive game at the time to develop, costing $145 million,[21] though $100 million was spent on marketing.[22] It used pre-rendered backgrounds and character models instead of 2D sprites, in addition to introducing full-motion video sequences.[note 1] Character models used on the field and those in battle differed, with blocky and less detailed models used on the field. When developing Final Fantasy VIII, Square Enix opted to use a more photo-realistic style, and there was no longer a distinction between field and battle models. The game used more FMVs, and required four discs of storage. Final Fantasy IX was similar, and though its art style was not one of a photorealistic game, it did allow for greater detail than seen previously in the series.

Example of facial expressions technology in Final Fantasy X.

The next three titles would be released on PlayStation 2. Due to the more advanced technology, the games no longer relied on pre-rendered backgrounds, instead using the game engine to render the backgrounds immediately. Final Fantasy X improved in the facial expressions displayed by the characters, using skeletal animation technology and motion capture, to allow the characters to make more realistic lip movements to match the new voice acting, a first in the series which previously was restricted to text-based story telling. The following release, Final Fantasy XI, was the first in the series to use online multiplayer features, which was another expensive development project for the company.[23] Final Fantasy XII would later use only half as many polygons as Final Fantasy X in exchange for improved lighting and texture rendering.[24]

When transitioning to the next generation of video game consoles, the now-merged Square Enix developed Final Fantasy XIII for PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360. It was developed using Crystal Tools, a proprietary engine built to develop games for the consoles. As the first high definition title, it allowed for a major improvement in graphics with many reviewers citing its visuals as a strong point.[25] [26] [27] The original release of Final Fantasy XIV was also developed using Crystal Tools, though its subsequent re-release, Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn, was developed using different technology.

A cutscene rendered using the Luminous Engine in Final Fantasy XV.

Final Fantasy XV is developed for the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One. It uses a new proprietary Luminous Engine, which was showcased during the demo Agni's Philosophy, and the engine early in development allowed the game to produce 5 million polygons per frame, with suggestions that the final game could be even more advanced.[28] Final Fantasy XVI is being developed as a PlayStation 5 exclusive.[29]

Reception [ ]

Critical reception [ ]

The series has overall enjoyed high critical acclaim, with varying success. Of the main series, six titles have reached a Metacritic score of or above 90: Final Fantasy VI at 91,[30] Final Fantasy VII at 92,[31] Final Fantasy VIII at 90,[32] Final Fantasy IX at 94,[33] Final Fantasy X at 92,[34] and Final Fantasy XII at 92.[35] The only game to reach a Metacritic score below 70 was the original Final Fantasy XIV launch at 49,[36], though the subsequent re-release, Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn, reached a score of 83.[37] The most critically acclaimed release was Final Fantasy IX,[33] while the poorest received by critics was the original Final Fantasy XIV.[36] Spinoffs, likewise, have enjoyed varied critical reception, though lower than that of the main series. Many spinoffs have been well received, such as Final Fantasy Tactics: The War of the Lions,[38] Dissidia 012 Final Fantasy,[39] and Theatrhythm Final Fantasy Curtain Call.[40] Many other spinoffs have been poorly received, such as Final Fantasy: All the Bravest,[41] Dirge of Cerberus -Final Fantasy VII-,[42] and Final Fantasy IV: The After Years.[43]

Titles in the series have generally received praise for their storylines, characters, settings, music, battle elements, and graphics.[44] [45] [25] Many other aspects in particular have received praise, such as the job system, a series staple,[46] [47] with GameSpot stating it is "hard to say enough good things" about it, referring to the the "exciting variety" it offers to the gameplay.[48] Another popular feature is the self-referential nature of many of the games and inclusions of allusions to previous games, with recurring features such as chocobos, moogles and Gilgamesh among others, being well received as nods to make fans feel at home.[49] [50] [51] The series has also been praised for its gameplay variety and innovation between installments to prevent the gameplay from going stale.[52] [53] [54]

The series has received criticism for many other aspects. Many have found the menu-based combat system and its use of random encounters to be a turnoff, or an outdated annoyance,[55] [56] with IGN stating the the use of random encounters "need[ed] to change".[57] The series' minigames have been divisive and often come under fire as weaker aspects[58] [59] [60] (although minigames have received praise in other regard[61]). Finally, many direct sequels in the series have been poorly received and believed to be worse than the original titles.[62] [63] [64]

Due to the large differences between the games in terms of setting and gameplay, opinions of games in the series tend to also differ greatly. As a result, when listing the best Final Fantasy games, many publications have very different listings, with the only real consensus being Final Fantasy VI almost always listed in first place and Final Fantasy VII being listed very highly, in many cases second place.[65] [66] [67] [68] [69]

Accolades [ ]

The series was the first series to win a Walk of Game star in 2006, for seeking perfection and for being a risk taker in innovation.[53] GameFAQs held a contest in 2006 for the best game series of all time in which Final Fantasy appeared just behind The Legend of Zelda at second place;[70] additionally, the site has listed Final Fantasy VII as the best game of all time in 2004's top 100 games list, and in a 2014, featured two titles in its top 100 games list.[note 2] [71] In 2006, IGN listed the Final Fantasy series as the third greatest series of all time;[72] the site also listed three titles in its top 100 games list,[note 3] [73] nine titles in its top 100 RPGs list [74] two titles in their top PlayStation 2 games list,[note 4] [75] and two titles in their top 25 SNES games list[note 5].[76]

WatchMojo.com has frequently placed titles in the series in top ten lists, including top 10 JRPGs of all time,[note 6] [77] top 10 PSOne games,[note 7] [78] top ten PSOne RPGs,[note 8] [79] top ten PlayStation games of all time,[note 9] [80] and top ten Super Nintendo RPGs.[note 10] [81] The series held seven Guinness World Records in its Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2008, including "Most Games in an RPG Series", "Longest Development Period",[note 11] and "Fastest Selling Console RPG in a Single Day";[82] in the subsequent issue in 2009, two titles in the series featured in its top 50 console games.[note 12] [83]

The music of the series composed by Nobuo Uematsu won the series a place in the Hall of Fame on Classic FM.[15]

Commercial performance [ ]

The series has become a commercial success, and is the best selling Square Enix franchise with over 130 million units sold worldwide.[2] This makes it one of the best selling franchises world-wide. The best selling title has been Final Fantasy VII, with 11 million copies sold as of October 2015,[7] and became the second best selling game on the PlayStation.[84] The second best-selling title in the series is Final Fantasy X with over 8.05 million units sold as of August 2015 (not including the Final Fantasy X/X-2 HD Remaster).[85] Meanwhile, Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn reached subscriber numbers of 5 million, making it the second most popular subscription-based MMO as of July 2015.[86] The mobile game Final Fantasy Record Keeper was downloaded over 5 million times in Japan alone as of August 2015.[87]

The success of Final Fantasy and its key role within Square Enix's business plan has served as a double-edged sword. The first movie in the franchise, Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, was a box office flop with a net loss of $72-102 million,[88] and delayed the merger between Square and Enix.[89] On the other hand, Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn was primarily responsible for overturning the company's financial losses at the end of 2013.[90]

Pop culture and legacy [ ]

The series' popularity has led to it having an impact in popular culture, with appearances and references in anime, TV, and film. The music in particular has garnered much attention, such as winning a place on the Classic FM Hall of Fame,[15] and a performance from synchronized swimmers at the 2004 Summery Olympics to "Liberi Fatali" from Final Fantasy VIII.

The series has spawned many spinoff franchises. The most notable, Kingdom Hearts, is a crossover between Final Fantasy characters and Disney characters, and has gone on to be successful in its own right with 21 million units sold.[91] Many games have been released by staff who previously worked on Final Fantasy titles. Bravely Default began as a spiritual successor to Final Fantasy: The 4 Heroes of Light, and includes the job system and similar abilities. The Last Story was developed by series creator Sakaguchi after leaving Square Enix, while Granblue Fantasy was developed by former staff and had a musical score composed by Nobuo Uematsu.

Notes [ ]

- ↑

An example of a full-motion video sequence in Final Fantasy VII. - ↑ Final Fantasy X at 10th and Final Fantasy VII at 3rd

- ↑ Final Fantasy VII at 80, Final Fantasy Tactics at 67 and Final Fantasy VI at 23

- ↑ Final Fantasy XII at 17 and Final Fantasy X at 5

- ↑ Final Fantasy II (IV) at 14 and Final Fantasy III (VI) at 4

- ↑ Final Fantasy VI at 2

- ↑ Final Fantasy VII at 4

- ↑ Final Fantasy VII at 1

- ↑ Final Fantasy VII at 4

- ↑ Final Fantasy VI at 2

- ↑ Awarded for Final Fantasy XII at the time

- ↑ Final Fantasy VII at 20, Final Fantasy XII at 8

References [ ]

- ↑ Final Fantasy series celebrates its 25th birthday (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Gadgets Magazine Phillipines

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Square Enix Kicks Off Final Fantasy 30th Anniversary Celebration (Accessed: June 27, 2017) at Square Enix Press Center

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 IGN Presents The History of Final Fantasy (Accessed: October 10, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ Final Fantasy was almost called Fighting Fantasy: Creator explains actual reason behind the name (Accessed: October 10, 2015) at Destructoid

- ↑ Masterpiece: Final Fantasy VII (Accessed: October 11, 2015) at Ars Technica

- ↑ Final Fantasy VII (Accessed: October 11, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Final Fantasy VII App on iTunes (Accessed: October 11, 2015) at Apple

- ↑ Hironobu Sakaguchi and Hajime Tabata Discuss Their Passion for the Series and Behind-the-Scenes Episodes from the Final Fantasy XV Reveal Event (Accessed: August 25, 2018) at Final Fantasy XV Famitsu.com Special Website

- ↑ Final Fantasy's Hiroyuki Ito and the Science of Battle (dead) ( Accessed: October 10, 2015 Retrieved from http://www.1up.com/features/final-fantasy-hiroyuki-ito-science ) at 1UP.com

- ↑ Final Fantasy VII – 1997 Developer Interviews (Accessed: October 10, 2015) at shmuplations

- ↑ FF to look like Advent Children? (Accessed: October 11, 2015) at Eurogamer.net

- ↑ Every Game is Hayao Miyazaki (dead) ( Accessed: October 10, 2015 Retrieved from http://www.1up.com/features/every-game-is-hayao-miyazaki ) at 1UP.com

- ↑ Every Final Fantasy is Star Wars (Accessed: October 10, 2015) at USgamer

- ↑ 14 Facts You May Not Know About 'Final Fantasy VII' (Accessed: October 10, 2015) at UPROXX

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Hall of Fame: Final Fantasy series (Accessed: October 16, 2015) at Classic FM

- ↑ Review: Nobuo Uematsu – Final Symphony (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at it's all dead

- ↑ Nobuo Uematsu Remembers 20 Years of Final Fantasy Soundtracks (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Nobuo Uematsu Interview (dead) ( Accessed: October 31, 2015 Retrieved from http://www.nobuouematsu.com/nobegm2.html ) at www.nobuouematsu.com (dead)

- ↑ Nobuo Uematsu interview by Yoshitake Maeda (dead) ( Accessed: October 31, 2015 Retrieved from http://www.nobuouematsu.com/yosh.html ) at www.nobuouematsu.com (dead)

- ↑ IGN Presents The History of Final Fantasy (Accessed: October 10, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ 20 of the Most Expensive Games Ever Made (dead) ( Accessed: October 03, 2015 Retrieved from http://www.gamespot.com/gallery/20-of-the-most-expensive-games-ever-made/2900-104/5/ ) at GameSpot

- ↑ Final Fantasy 7 retrospective (Accessed: September 24, 2015) at Eurogamer.net

- ↑ Final Fantasy XI: Big Plans, Big Money (Accessed: September 02, 2017) at IGN

- ↑ Final Fantasy XII Preview (dead) ( Accessed: November 03, 2015 Retrieved from http://www.1up.com/previews/final-fantasy-xii_19 ) at 1UP.com

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Final Fantasy XIII Review (Accessed: October 24, 2015) at GamesRadar

- ↑ Final Fantasy XIII Review (Accessed: September 30, 2015) at GameSpot

- ↑ Final Fantasy XIII Review (Accessed: September 01, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ Final Fantasy 15 Receives Information Drop On Polygons, Bone Count, Luminous Engine & More (Accessed: November 18, 2015) at GamingBolt.com

- ↑ Naoki Yoshida, Hiroshi Takai (September 16, 2020). Final Fantasy XVI announced for PS5. PlayStation Blog. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020.

- ↑ Final Fantasy VI for iOS reviews (Accessed: October 27, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Final Fantasy VII for PlayStaion reviews (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Final Fantasy VIII for PlayStation reviews (Accessed: September 26, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Final Fantasy IX for PlayStation reviews (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Final Fantasy X for PlayStation 2 reviews (Accessed: November 05, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Final Fantasy XII for PlayStation 2 reviews (Accessed: November 01, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Final Fantasy XIV Online for PC reviews (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn for PC reviews (Accessed: October 26, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Final Fantasy Tactics: The War of the Lions for PSP reviews (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Dissidia 012: Duodecim Final Fantasy for PSP reviews (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Theatrhythm Final Fantasy: Curtain Call for 3DS reviews (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Final Fantasy: All the Bravest for iOS reviews (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Dirge of Cerberus: Final Fantasy VII for PlayStation 2 reviews (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Final Fantasy IV: The After Years for iOS reviews (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Metacritic

- ↑ Final Fantasy VII Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ Final Fantasy X Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at GameSpot

- ↑ Final Fantasy Dimensions Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ Final Fantasy Tactics: War of the Lions Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Eurogamer

- ↑ Final Fantasy V Advance Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at GameSpot

- ↑ Final Fantasy IX Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at GameSpot

- ↑ Final Fantasy 14: A Realm Reborn Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at GamesRadar

- ↑ Dissidia Final Fantasy Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at GameSpot

- ↑ The Innovation of Final Fantasy: Hits and Misses (dead) ( Accessed: October 31, 2015 Retrieved from http://www.g4tv.com/thefeed/blog/post/721825/the-innovation-of-final-fantasy-hits-and-misses/ ) at G4 (dead)

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 2006 Walk of Game Inductees (dead) ( Accessed: July 01, 2008 Retrieved from http://www.walkofgame.com/inductees/inductees.html ) at WalkofGame.com (dead)

- ↑ Final Fantasy 15 Isn't Afraid to Innovate to Find Greatness (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ The Evolution of Final Fantasy (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ Five Things I Like (And Five Things I Don't Like) About The Latest Final Fantasy Game (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Kotaku

- ↑ Final Fantasy IX Review (Accessed: October 28, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ 5 reasons to hate Final Fantasy (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at GamesRadar

- ↑ Top 5 Most Excruciating Final Fantasy Minigames (dead) ( Accessed: June 11, 2015 Retrieved from http://www.twinfinite.net/2014/05/26/top-5-painful-excruciating-mini-games-final-fantasy/ ) at Twinfinite

- ↑ Final Fantasy X-2 Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at GameSpot

- ↑ Top 5 Most Enjoyable Final Fantasy Minigames (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Twinfinite

- ↑ Final Fantasy IV: The After Years Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at GameSpot

- ↑ Dirge of Cerberus: Final Fantasy VII Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ Final Fantasy XIII-2 Review (Accessed: November 01, 2015) at PC Gamer

- ↑ Top 10 Final Fantasy Video Games (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at WatchMojo.com

- ↑ The 25 best Final Fantasy games (Accessed: November 07, 2015) at GamesRadar

- ↑ Ranking the Final Fantasy series (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ Top 10 Final Fantasy Games Of All Time (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Gamingbolt

- ↑ The Shockingly Hard Best to Worst Ranked Final Fantasy Games (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Giant Bomb

- ↑ Summer 2006: Best. Series. Ever. (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at GameFAQs

- ↑ The Top 100 Games of All Time, According to GameFAQs (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at GameFAQs

- ↑ The Top 25 Videogame Franchises (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ The Top 100 Video Games of All Time (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ Top 100 RPGs of All Time (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ The Top 25 PS2 Games of All Time (Accessed: October 17, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ The Top 100 SNES Games of All Time (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at IGN

- ↑ Top 10 JRPGs of All Time (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at WatchMojo.com

- ↑ Top 10 JRPGs of All Time (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at WatchMojo.com

- ↑ Top 10 Playstation 1 RPGs (Accessed: November 18, 2015) at WatchMojo.com

- ↑ Top 10 PlayStation Games of All Time (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at WatchMojo.com

- ↑ Top 10 Super Nintendo RPGs (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at WatchMojo.com

- ↑ wikipedia:Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2008, p.157-167

- ↑ wikipedia:Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2009, p.190-191

- ↑ Final Fantasy VII Steam Review (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Eurogamer.net

- ↑ Final Fantasy X (PlayStation 2) (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at VGChartz

- ↑ Final Fantasy XIV Has Had 5 Million Subscribers, Is Second Most Popular Subscription-Based MMO (Accessed: October 18, 2015) at GameRevolution

- ↑ FINAL FANTASY Record Keeper (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at Google Play Store

- ↑ Greatest Box-Office Bombs, Disasters and Film Flops (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at filmsite

- ↑ Square-Enix Gives Chrono Break Trademark Some Playmates (dead) ( Accessed: October 31, 2015 Retrieved from http://www.rpgamer.com/news/Q2-2003/042503e.html ) at RPGamer

- ↑ Square Enix's Final Fantasy XIV Saves Its Profit Margin (Accessed: October 31, 2015) at The Escapist

- ↑ Square Enix Businesses Holdings (Accessed: October 10, 2015) at Square Enix Holdings

External links [ ]

- Final Fantasy on Wikipedia

Videos For Final Fantasy Game Design

Source: https://finalfantasy.fandom.com/wiki/Final_Fantasy_series

Posted by: dixonsatereat.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Videos For Final Fantasy Game Design"

Post a Comment